This is a guest post by Michael Hüttermann. Michael is an expert in Continuous Delivery, DevOps and SCM/ALM. More information about him at huettermann.net, or follow him on Twitter: @huettermann. |

In a past blog post Delivery Pipelines, we talked about pipelines which result in binaries for development versions. Now, in this blog post, I zoom in to different parts of the holistic pipeline and cover the handling of possible downstream steps once you have the binaries of development versions, in our example a Java EE WAR and a Docker image (which contains the WAR). We discuss basic concept of staging software, including further information about quality gates, and show example toolchains. This contribution particularly examines the staging from binaries from dev versions to release candidate versions and from release candidate versions to final releases from the perspective of the automation server Jenkins, integrating with the binary repository manager JFrog Artifactory and the distribution management platform JFrog Bintray, and ecosystem.

Staging software

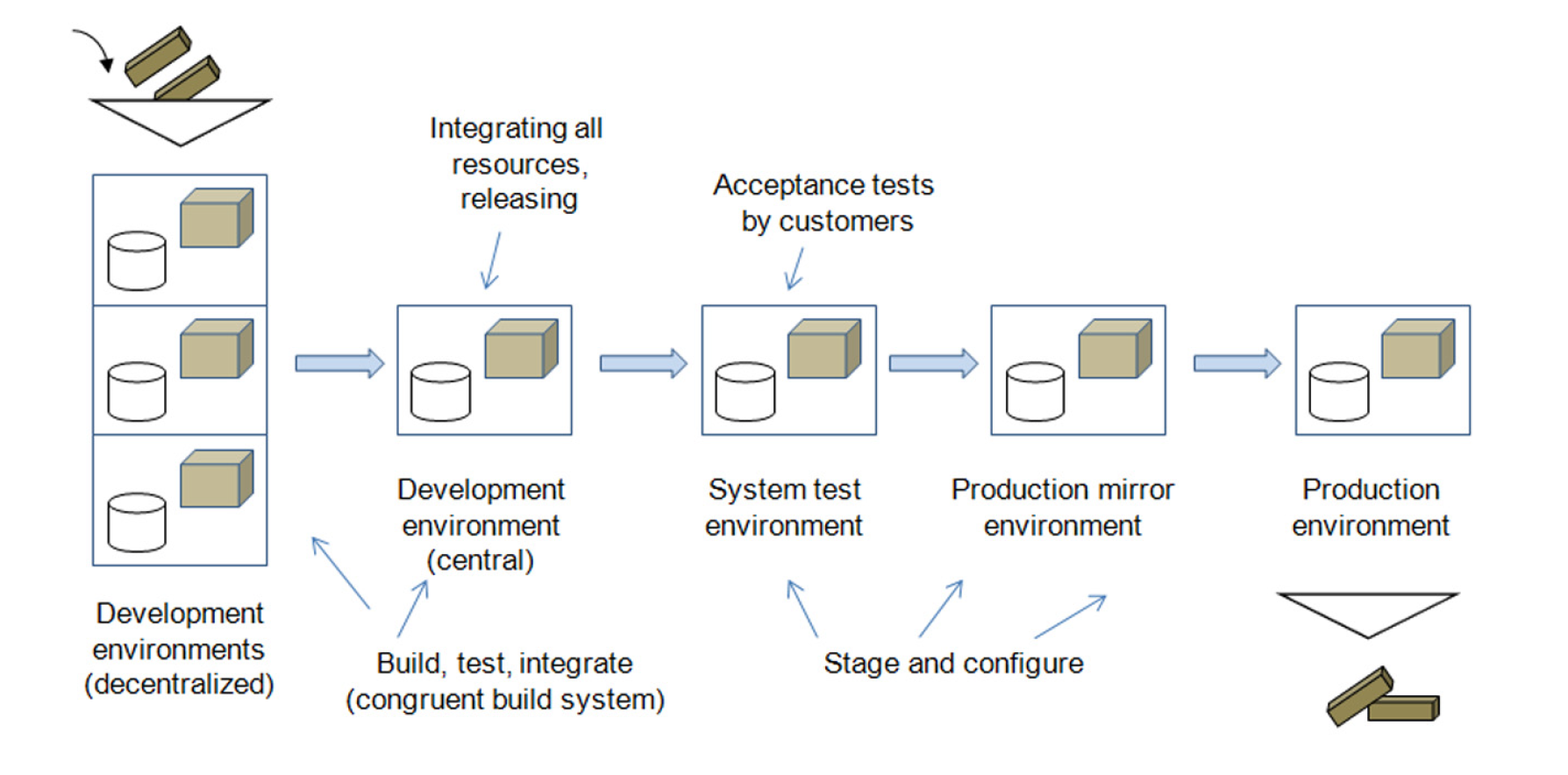

Staging (also often called promoting) software is the process of completely and consistently transferring a release with all its configuration items from one environment to another. This is even more true with DevOps, where you want to accelerate the cycle time (see Michael Hüttermann, DevOps for Developers (Apress, 2012), 38ff). For accelerating the cycle time, meaning to bring software to production, fast and in good quality, it is crucial to have fine processes and integrated tools to streamline the delivery of software. The process of staging releases consists of deploying software to different staging levels, especially different test environments. Staging also involves configuring the software for various environments without needing to recompile or rebuild the software. Staging is necessary to transport the software to production systems in high quality. Many Agile projects make great experience with implementing a staging ladder in order to optimize the cycle time between development software and the point when the end user is able to use the software in production.

Commonly, the staging ladder is illustrated on its side, with the higher rungs being the boxes further to the right. It’s good practice not to skip any rungs during staging. The central development environment packages and integrates all respective configuration items and is the base for releasing. Software is staged over different environments by configuration, without rebuilding. All changes go through the entire staging process, although defined exception routines may be in place, for details see Michael Hüttermann, Agile ALM (Manning, 2012).

To make concepts clearer, this blog post covers sample tools. Please note, that there are also alternative tools available. As one example: Sonatype Nexus is also able to host the covered binaries and also offers scripting functionality. |

We nowadays often talk about delivery pipelines. A pipeline is just a set of stages and transition rules between those stages. From a DevOps perspective, a pipeline bridges multiple functions in organizations, above all development and operations. A pipeline is a staging ladder. A change enters the pipeline at the beginning and leaves it at the end. The processing can be triggered automatically (typical for delivery pipelines) or by a human actor (typical for special steps at overall pipelines, e.g. pulling and thus cherry-picking specific versions to promote them to be release candidates are final releases).

Pipelines often look different, because they strongly depend on requirements and basic conditions, and can contain further sub pipelines. In our scenario, we have two sub pipelines to manage the promotion of continuous dev versions to release candidates and the promotion of release candidates to final release. A change typically waits at a stage for further processing according to the transition rules, aligned with defined requirements to meet, which are the Quality Gates, explored next.

Quality Gates

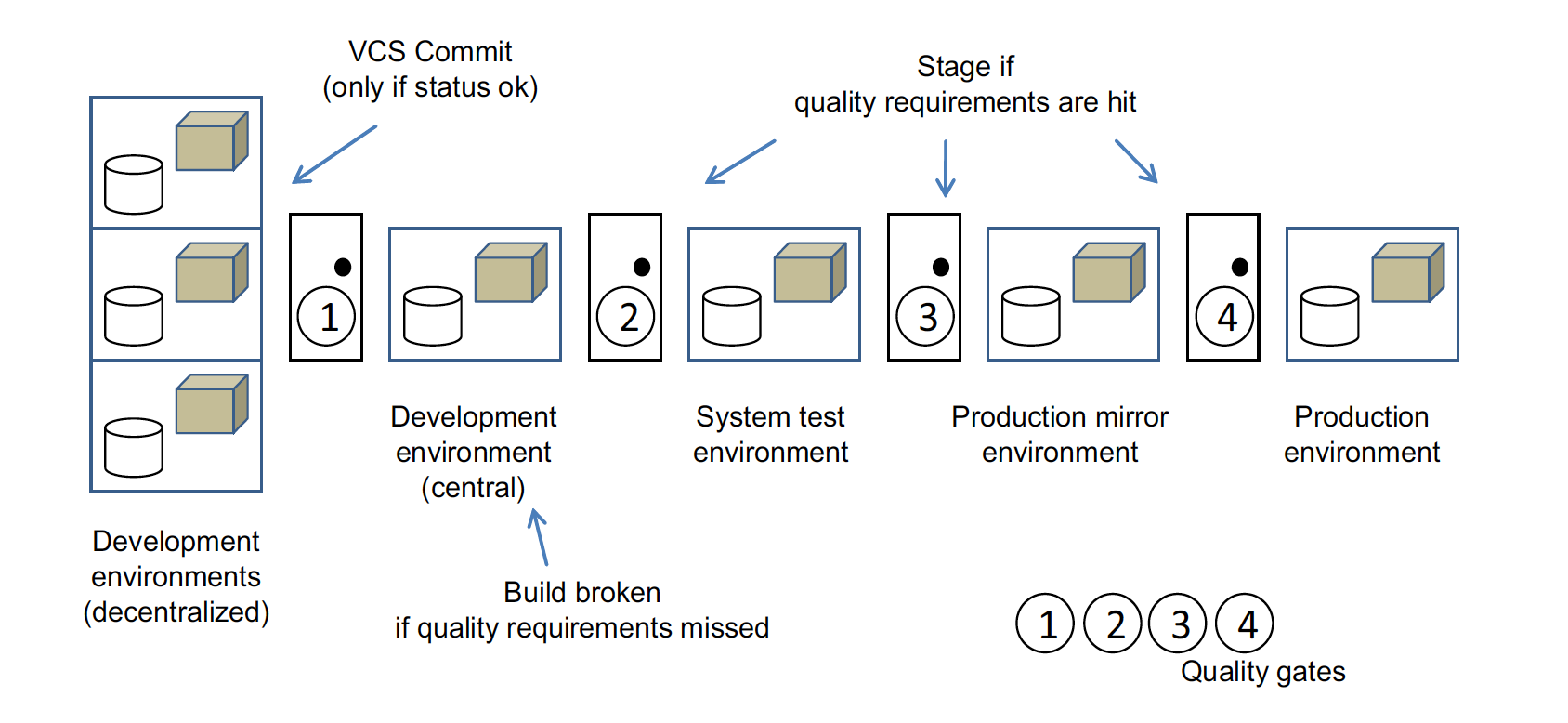

Quality gates allow the software to pass through stages only if it meets their defined requirements. The next illustration shows a staging ladder with quality gates injected. You and other engaged developers commit code to the version control system (please, use VCS as an abbreviation, not SCM, because the latter is much more) in order to update the central test environment only if the code satisfies the defined quality requirements; for instance, the local build may need to run successfully and have all tests pass locally. Build, test, and metrics should pass out of the central development environment, and then automated and manual acceptance tests are needed to pass the system test. In our case, the last quality gate to pass is the one from the production mirror to production. Here, for example, specific production tests are done or relevant documents must be filled in and signed.

It’s mandatory to define the quality requirements in advance and to resist customizing them after the fact, when the software has failed. Quality gates are different at lower and higher stages; the latter normally consist of a more severe or broader set of quality requirements, and they often include the requirements of the lower gates. The binary respository manager must underpin corresponding quality gates, while managing the binaries, what we cover next.

This blog post illustrates typical concepts and sample toolchains. For more information, please consult the respective documentation, good books or attend top notch conferences, e.g.Jenkins World, powered by CloudBees. |

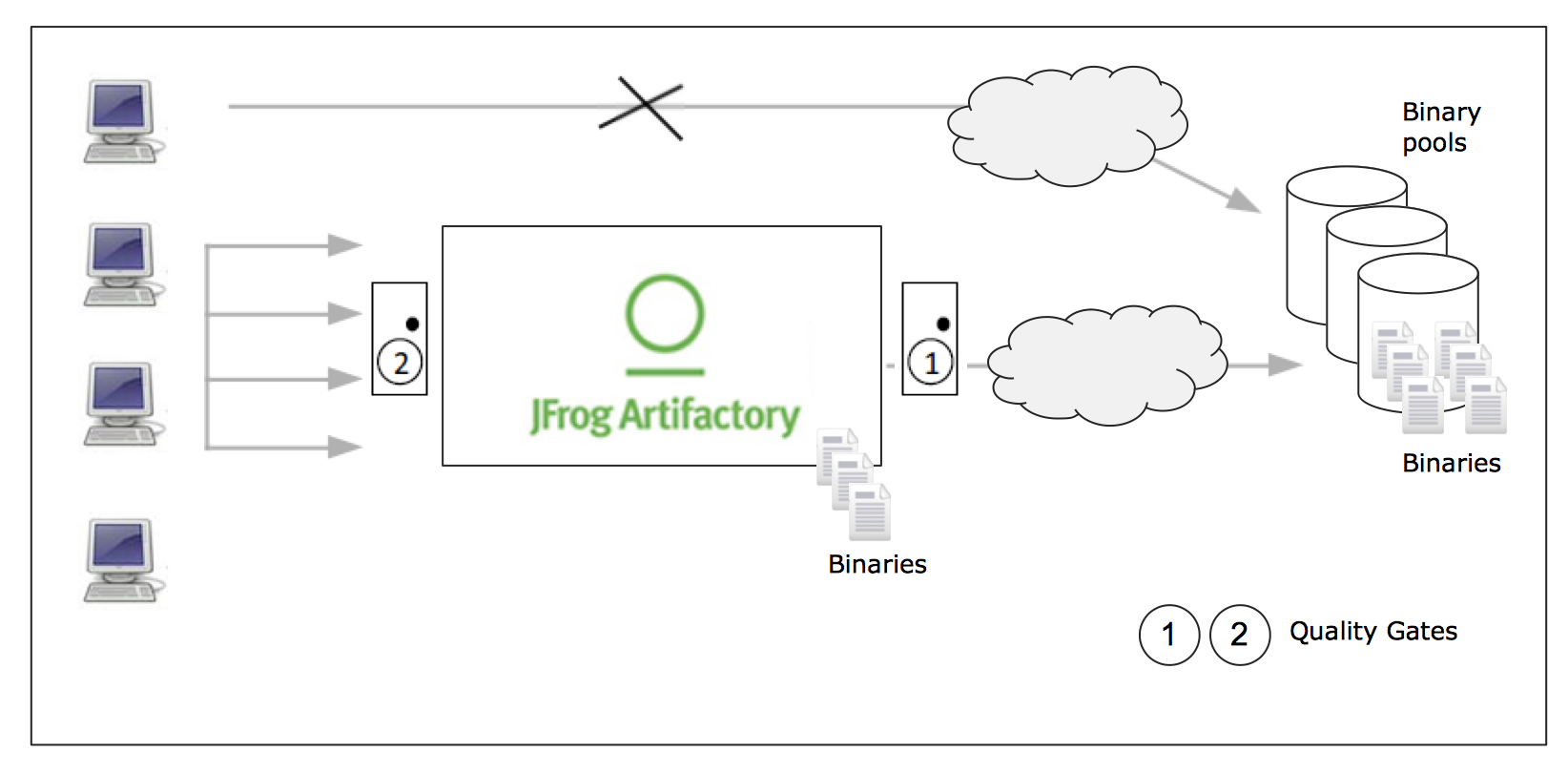

Binary repository manager

A central backbone of the staging ladder is the binary repository manager, e.g. JFrog Artifactory. The binary repository manager manages all binaries including the self-produced ones (producing view) and the 3rd party ones (consuming view), across all artifact types, in our case a Java EE WAR file and a Docker image. Basic idea here is that the repo manager serves as a proxy, thus all developers access the repo manager, and not remote binary pools directly, e.g. Maven Central. The binary repository manager offers cross-cutting services, e.g. role-based access control on specific logical repositories, which may correspond to specific stages of the staging ladder.

Logical repositories can be generic ones (meaning they are agnostic regarding any tools and platforms, thus you can also just upload the menu of your local canteen) or repos specific to tools and platforms. In our case, we need a repository for managing the Java EE WAR files and for the Docker images. This can be achieved by

a generic repository (prefered for higher stages) or a repo which is aligned with the layout of the Maven build tool, and

a repository for managing Docker images, which serves as a Docker registry.

In our scenario, preparing the staging of artifacts includes the following ramp-up activities

Creating two sets of logical repositories, inside JFrog Artifactory, where each set has a repo for the WAR file and a repo for the Docker image, and one set is for managing dev versions and one set is for release candidate versions.

Defining and implementing processes to promote the binaries from the one set of repositories (which is for dev versions) to the other set of repositories (which is for RC versions). Part of the process is defining roles, and JFrog Artifactory helps you to implement role-based access control.

Setting up procedures or scripts to bring binaries from one set of repositories to the other set of repositories, reproducibly. Adding meta data to binaries is important if the degree of maturity of the binary cannot be easily derived from the context.

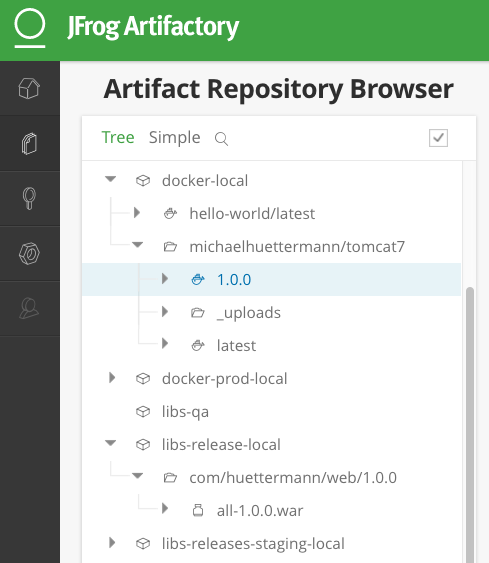

The following illustration shows a JFrog Artifactory instance with the involved logical repos in place. In our simplified example, the repo promotions are supposed to go fromdocker-local to docker-prod-local, and from libs-release-local to libs-releases-staging-local. In our use case, we promote the software in version 1.0.0.

Another type of binary repository manager is JFrog Bintray, which serves as a universal distribution platform for many technologies. JFrog Bintray can be an interesting choice if you have strong requirements for scalability and worldwide coverage including IP restrictions and handy features around statistics. Most of the concepts and ramp up activities are similar compared to JFrog Artifactory, thus I do not want to repeat them here. Bintray is used by lot of projects e.g. by Groovy, to host their deliverables in the public. But keep in mind that you can of course also host your release binaries in JFrog Artifactory. In this blog post, I’d like to introduce different options, thus we promote our release candidates to JFrog Artifactory and our releases to JFrog Bintray. Bintray has the concept of products, packages and versions. A product can have multiple packages and has different versions. In our example, the product has two packages, namely the Java EE WAR and the Docker image, and the concrete version that will be processed is 1.0.0.

Some tool features covered in this blog post are avaialable as part of commercial offerings of tool vendors. Examples include the Docker support of JFrog Artifactory or the Firehose Event API of JFrog Bintray. Please consult the respective documentation for more information. |

Now it is time to have a deeper look at the pipelines.

Implementing Pipelines

Our example pipelines are implemented with Jenkins, including its Blue Ocean and declarative pipelines facilities, JFrog Artifactory and JFrog Bintray. To derive your personal pipelines, please check your individual requirements and basic conditions to come up with the best solution for your target architecture, and consult the respective documentation for more information, e.g. about scripting the tools.

In case your development versions are built with Maven, and have SNAPSHOT character, you need to either rebuild the software after setting the release version, as part of your pipeline, or you solely use Maven releases from the very beginning. Many projects make great experience with morphing Maven snapshot versions into release versions, as part of the pipeline, by using a dedicated Maven plugin, and externalizing it into a Jenkins shared library. This can look like the following:

#!/usr/bin/groovy

def call(args) { (1)

echo "Calling shared library, with ${args}."

sh "mvn com.huettermann:versionfetcher:1.0.0:release versions:set -DgenerateBackupPoms=false -f ${args}" (2)

}| 1 | We provide a global variable/function to include it in our pipelines. |

| 2 | The library calls a Maven plugin, which dynamically morphs the snapshot version of a Maven project to a release version. |

And including it into the pipeline is then also very straight forward:

stage('Produce RC') { (1)

releaseVersion 'all/pom.xml' (2)

}| 1 | This stage is part of a scripted pipeline and is dedicated to morphing a Maven snapshot version into a release version, dynamically. |

| 2 | We call the Jenkins shared library, with a parameter pointing to the Maven POM file, which can be a parent POM. |

You can find the code of the underlying Maven plugin here.

Let’s now discuss how to proceed for the release candidates.

Release Candidate (RC)

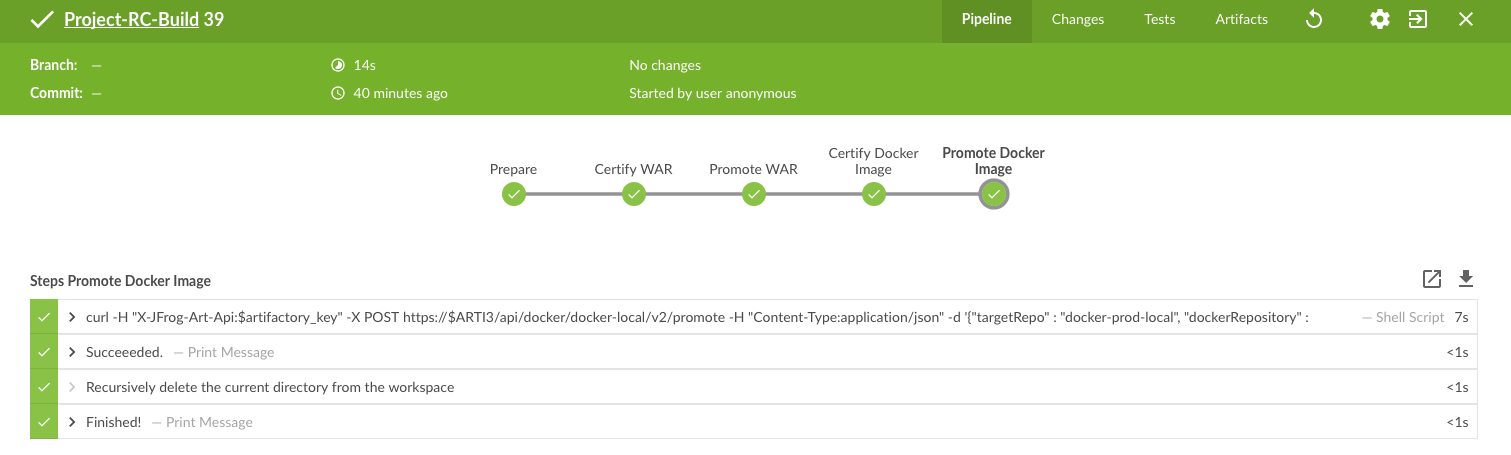

The pipeline to promote a dev version to a RC version does contain a couple of different stages, including stages to certify the binaries (meaning labeling it or adding context information) and stages to process the concrete promotion. The following illustration shows the successful run of the promotion, for software version 1.0.0.

We utilize Jenkins Blue Ocean that is a new user experience for Jenkins based on a personalizable, modern design that allows users to graphically create, visualize and diagnose delivery pipelines. Besides the new approach in general, single Blue Ocean features help to boost productivity dramatically, e.g. to provide log information at your fingertips and the ability to search pipelines. The stages to perform the promote are as follows starting with the Jenkins pipeline stage for promoting the WAR file. Keep in mind that all scripts are parameterized, including variables for versions and Artifactory domain names, which are either injected to the pipeline run by user input or set system wide in the Jenkins admin panel, and the underlying call is using the JFrog command line interface, CLI in short. JFrog Artifactory as well as JFrog Bintray can be used and managed by scripts, based on a REST API. The JFrog CLI is an abstraction on top of the JFrog REST API, and we show sample usages of both.

stage('Promote WAR') { (1)

steps { (2)

sh 'jfrog rt cp --url=https://$ARTI3 --apikey=$artifactory_key --flat=true libs-release-local/com/huettermann/web/$version/ ' + (3)

'libs-releases-staging-local/com/huettermann/web/$version/'

}

}| 1 | The dedicated stage for running the promotion of the WAR file. |

| 2 | Here we have the steps which make up the stage, based on Jenkins declarative pipeline syntax. |

| 3 | Copying the WAR file, with JFrog CLI, using variables, e.g. the domain name of the Artifactory installation. Many options available, check the docs. |

The second stage to explore more is the promotion of the Docker image. Here, I want to show you a different way how to achieve the goal, thus in this use case we utilize the JFrog REST API.

stage('Promote Docker Image') {

sh '''curl -H "X-JFrog-Art-Api:$artifactory_key" -X POST https://$ARTI3/api/docker/docker-local/v2/promote ''' + (1)

'''-H "Content-Type:application/json" ''' + (2)

'''-d \'{"targetRepo" : "docker-prod-local", "dockerRepository" : "michaelhuettermann/tomcat7", "tag": "\'$version\'", "copy": true }\' (3)

'''

}| 1 | The shell script to perform the staging of Docker image is based on JFrog REST API. |

| 2 | Part of parameters are sent in JSON format. |

| 3 | The payload tells the REST API endpoint what to to, i.e. gives information about target repo and tag. |

Once the binaries are promoted (and hopefully deployed and tested on respective environments before), we can promote them to become final releases, which I like to call GA.

General Availability (GA)

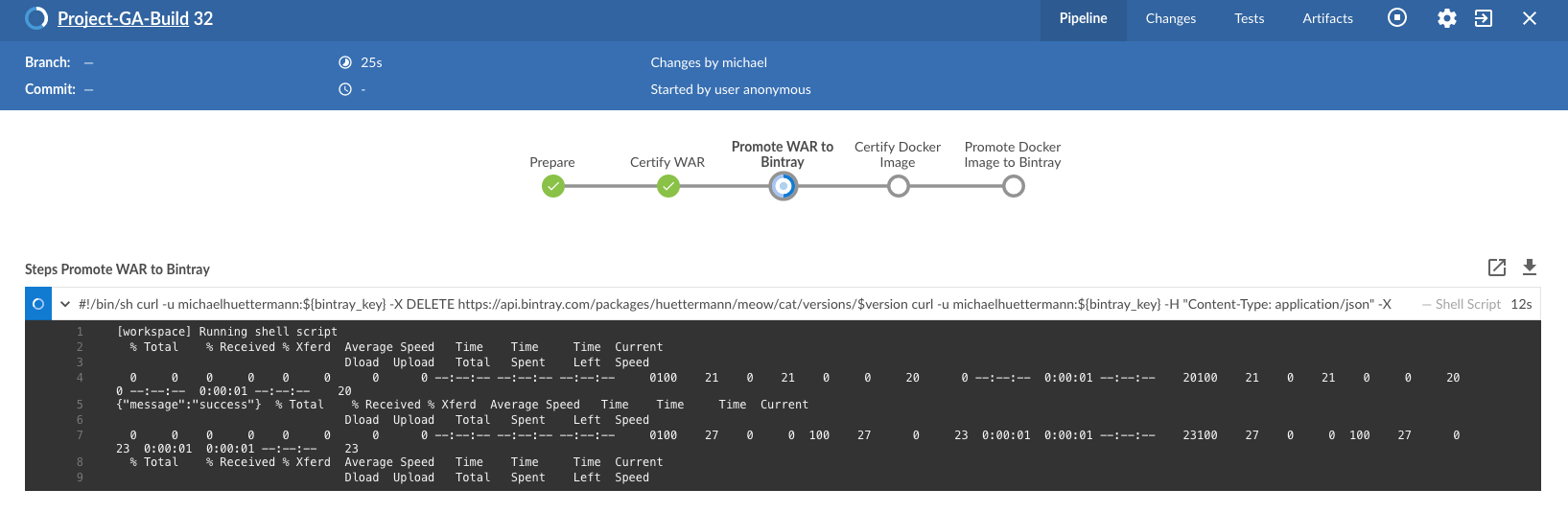

In our scenario, JFrog Bintray serves as the distribution platform to manage and provide binaries for further usage. Bintray can also serve as a Docker registry, or can just provide binaries for scripted or manual download. There are again different ways how to promote binaries, in this case from the RC repos inside JFrog Artifactory to the GA storage in JFrog Bintray, and I summarize one of those possible ways. First, let’s look at the Jenkins pipeline, showed in the next illustration. The processing is on its way, currently, and we again have a list of linked stages.

Zooming in now to the key stages, we see that promoting the WAR file is a set of steps that utilize JFrog REST API. We download the binary from JFrog Artifactory, parameterized, and upload it to JFrog Bintray.

stage('Promote WAR to Bintray') {

steps {

sh '''

curl -u michaelhuettermann:${bintray_key} -X DELETE https://api.bintray.com/packages/huettermann/meow/cat/versions/$version (1)

curl -u michaelhuettermann:${bintray_key} -H "Content-Type: application/json" -X POST https://api.bintray.com/packages/huettermann/meow/cat/$version --data """{ "name": "$version", "desc": "desc" }""" (2)

curl -T "$WORKSPACE/all-$version-GA.war" -u michaelhuettermann:${bintray_key} -H "X-Bintray-Package:cat" -H "X-Bintray-Version:$version" https://api.bintray.com/content/huettermann/meow/ (3)

curl -u michaelhuettermann:${bintray_key} -H "Content-Type: application/json" -X POST https://api.bintray.com/content/huettermann/meow/cat/$version/publish --data '{ "discard": "false" }' (4)

'''

}

}| 1 | For testing and demo purposes, we remove the existing release version. |

| 2 | Next we create the version in Bintray, in our case the created version is 1.0.0. The value was insert by user while triggering the pipeline. |

| 3 | The upload of the WAR file. |

| 4 | Bintray needs a dedicated publish step to make the binary publicy available. |

Processing the Docker image is as easy as processing the WAR. In this case, we just push the Docker image to the Docker registry, which is served by JFrog Bintray.

stage('Promote Docker Image to Bintray') { (1)

steps {

sh 'docker push $BINTRAYREGISTRY/michaelhuettermann/tomcat7:$version' (2)

}

}| 1 | The stage for promoting the Docker image. Please note, depending on your setup, you may add further stages, e.g. to login to your Docker registry. |

| 2 | The Docker push of the specific version. Note, that also here all variables are parameterized. |

We now have promoted the binaries and uploaded them to JFrog Bintray. The overview page of our product lists two packages: the WAR file and the Docker image. Both can be downloaded now and used, the Docker image can be pulled from the JFrog Bintray Docker registry with native Docker commands.

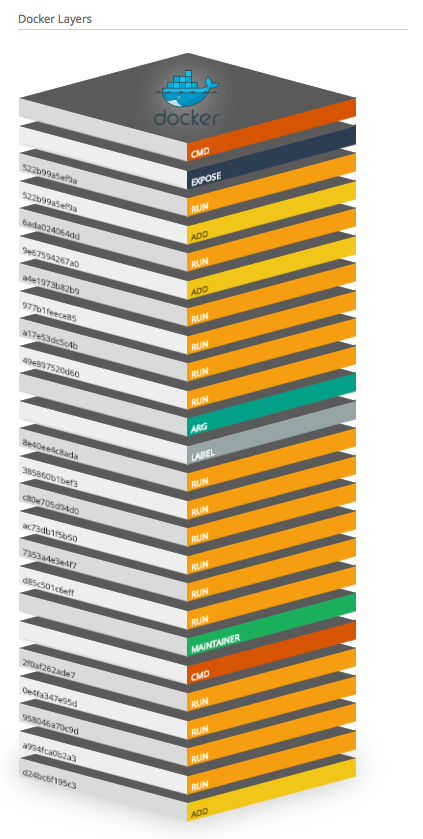

As part of its graphical visualization capabilitites, Bintray is able to show the single layers of the uploaded Docker images.

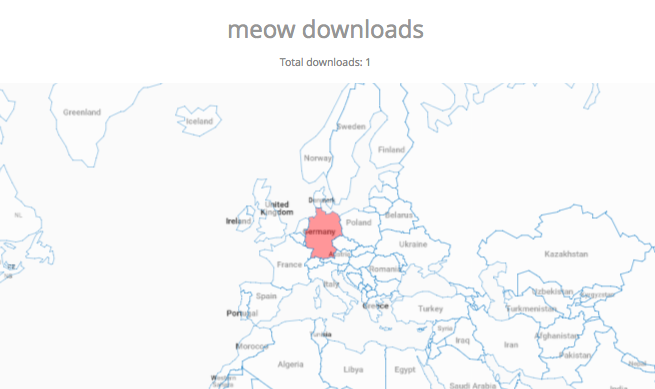

Bintray can also display usage statistics, e.g. download details. Now guess where I’m sitting right now while downloading the binary?

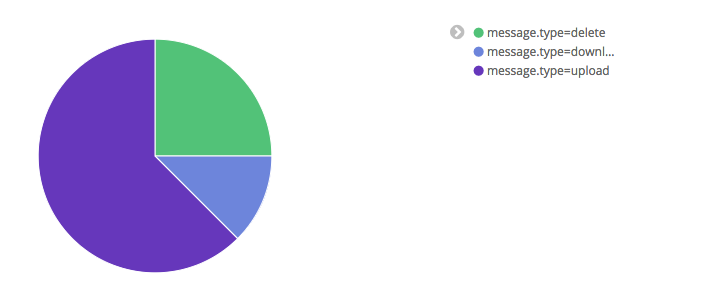

Besides providing own statistics, Bintray provides the JFrog Firehose Event API. This API streams live usage data, which in turn can be integrated or aggregated with your ecosystem. In our case, we visualize the data, particularly download, upload, and delete statistics, with the ELK stack, as part of a functional monitoring initiative.

Crisp, isn’t it?

Summary

This closes are quick ride through the world of staging binaries, based on Jenkins. We’ve discussed concepts and example DevOps enabler tools, which can help to implement the concepts. Along the way, we discussed some more options how to integrate with ecosystem, e.g. releasing Maven snapshots and functional monitoring with dedicated tools. After this appetizer you may want to now consider to double-check your staging processes and toolchains, and maybe you find some room for further adjustments.