| This is a speaker blog post for a DevOps World | Jenkins World 2019 talk in Lisbon, Portugal and has been posted in line with NCC Group responsible disclosure policy. Related Jenkins security advisories:2017-11-08,2017-11-16,2018-06-25,2018-07-30,2018-09-25,2019-02-19,2019-03-06,2019-03-25,2019-04-03,2019-04-17,2019-08-07,2019-09-12,2019-10-01,2019-10-16,2019-10-23. Some of the vulnerabilities have been announced without a fix, see Jenkins Security Spring Cleaning 2019. The most of the announced vulnerabilities are fixed at the moment of this blogpost publishing. |

Come join us at DevOps World | Jenkins World 2019 for "The Story, the Findings and the Fixes Behind More than 100 Jenkins Plugins Vulnerabilities", a talk about the most common vulnerabilities found during research in more than 100 plugins. We’ll review how to prevent these vulnerabilities during plugin development so that a more secure Jenkins CI and CD environment can be built.

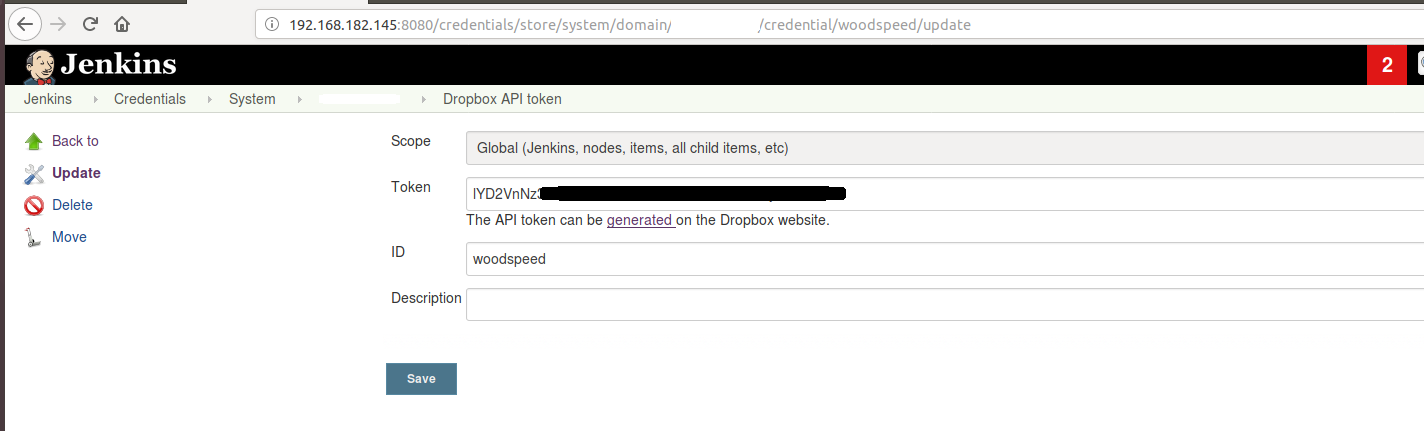

When I first began familiarising myself with Jenkins, I found myself almost overwhelmed by the amount of plugins to choose from. Most of these plugins are developed by third party developers or companies and can assist the user in a range of ways. They can extend the core functions, they can offer solutions to repetitive tasks or they can help with using a service. For example, they could help with publishing to an artifact store or spinning up cloud instances. However, before a plugin can use a network based service that requires credentials to connect, those credentials have to be typed in and saved somewhere. This raises the question, are those credentials stored securely? Or not? When I started looking at different plugins this was one of the first areas I investigated. I found a Jenkins security advisory describing this issue and came to the conclusion that this could be a problem in some plugins, albeit one that could be fixed easily. I found an example of weakly stored credentials in the Publish Over Dropbox Plugin; this plugin used a simple web form with a textbox element to display the token in the plugin’s settings page. This token was stored in plaintext:

The following Jelly code was behind the web form and shows that a password field wasn’t used:

<f:entrytitle="${%Token}"field="authorizationCode"><f:textbox/>The related plugin .xml file contained the secret key in plaintext:

<org.jenkinsci.plugins.publishoverdropbox.impl.DropboxTokenImplplugin="publish-over-dropbox@1.2.2"><scope>GLOBAL</scope><id>woodspeed</id><description></description><authorizationCode>lYD2VnNz</authorizationCode><accessCode>lYD2VnNz</accessCode></org.jenkinsci.plugins.publishoverdropbox.impl.DropboxTokenImpl>Jenkins offers at least two ways to store credentials in an encrypted format:

Using a Secret type offered by Jenkins

Third party plugin called Credentials Plugin

The first case is the easiest solution, because Jenkins will automatically handle the encryption and decryption.

Developers should also use the password field tag instead of the textbox field, as shown in the following Jelly control example:

<f:entrytitle="${%Secret Access Key}"help="..."><f:passwordfield="secretKey"/></f:entry>If you would like to know what other vulnerabilities I discovered and how to fix them, come and join us for the presentation in Lisbon! In case you are unable to attend the conference, you can read more at Story of a Hundred Vulnerable Jenkins Plugins.